The Society of St. John the Baptist

Our history

THE ORIGINS

Heir of the Opera di San Giovanni, an association with which – since 1157 – the Arte dei Calimala had curated the events in honor of the Patron Saint of Florence, the Society of St. John the Baptist was established with a “rescript” of January 29, 1796 by Grand Duke Ferdinand III of Tuscany. The young sovereign wanted to connect his figure to the most ancient Florentine tradition and the cult of the Baptist was always present in him in the most heartfelt forms. The same coins minted starting from 1791, according to a well-established practice, reported on the surface the image of St. John and the patron saint of the city was also the patron saint of the Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo and of the same Ferninando III of Lorraine.

The most violent years of the French Revolution were marked by the process of “de-Christianization”, which led to the disappearance of the Gregorian calendar and saw the disappearance of every saint. The assassination of the King of France, Luigi XVI, in January 1793, however, shook public opinion and, in the wake of these events, the idea of the constitution of a free secular and private association began to make its way in Florence, able to make the image of the Baptist more alive and to emphasize a spirituality without borders. On 12 November 1795 the Provveditore dell’Opera del Duomo, Pietro Pannilini, received a petition on behalf of a group of citizens, to be forwarded to Ferdinand III. In the petition it was hoped to “make the solemnity of St. John the Baptist more decorous” by proposing “decent music” to be played on the morning of the feast of the nativity of the Saint in the church dedicated to him. Ferdinand III did not hesitate to approve what was proposed and a letter was immediately printed to collect the first subscriptions: from February to June 1796 the adhesions collected were numerous and many Florentines of all classes responded generously. The cult of St. John now united, without distinction, nobles, bourgeois and wealthy commoners.

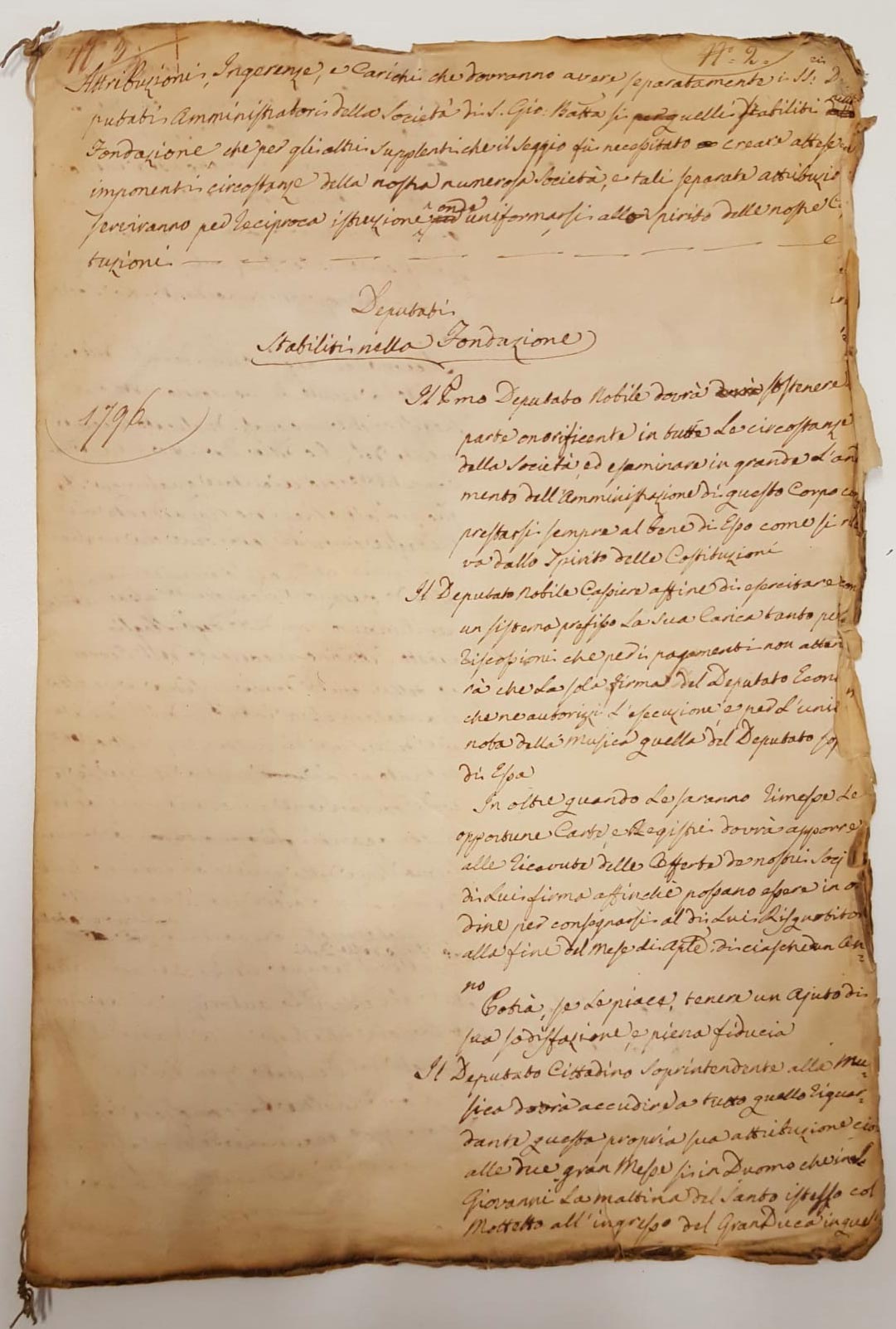

FIRST CONSTITUTIONS

It was necessary to involve popular favor around the new institution, and therefore until 1797 it was decided to include among the peculiar activities of San Giovanni the collection of alms for the constitution of dowries. The dowry, even in cases of marriages

socially modest, it was an essential requirement.

The goal was soon achieved and the popularity of San Giovanni grew progressively: the Society, understood as “Societas” – collectivity – ended up being one of the institutions closest to the spiritual and social reality of Florence.

The members of the association grew with the passing of the months and in 1798, since the number of 300 adhesions had already been exceeded, it was already possible to assign four dowries.

The devotional as well as secular character of the institution was evident and from the beginning it was considered opportune to ask Pope Pius VI to grant indulgences for the members of the Society.

NAPOLEONIC AGE

The tumultuous Napoleonic events also overwhelmed Tuscany but, with the creation of the Kingdom of Etruria, the Society of St. John the Baptist had new lifeblood.

King Louis of Bourbon and his wife Maria Luisa, dominated by a deep faith, gave the maximum impetus to every devotional manifestation and carefully took care of the feast of the patron saint of the city.

In particular, in that year an exceptional fireworks display was established: these fireworks “met the genius of the public for the variety and expressive execution (…) having been executed by the skilled firefighters Luigi Geraudini of Livorno and Luigi Badii”. The years 1806 and 1807 saw the maximum consecration of the patronal feasts, and the event assumed real traits of royal munificence.

Even in the years of the suppression of the Kingdom of Etruria, the Society of St. John the Baptist maintained its identity and the cult of the party was practiced at the public level with the performance of refined music in the Baptistery and with the usual distribution of dowries.

RESTORATION

The Restoration, in September 1814, saw the complete restoration of the festivities in honor of the Saint.

The Napoleonic age and the ideals of the Revolution had French deeply affected European society, and even in Tuscany a new climate had been created. The Restoration restored the power of the ancient dynasties, but not the real power of those social classes that had been fought by the Revolution.

Even the Florentine patronal celebrations soon changed character, assuming connotations of modest importance. The Society of St. John tried to draw the attention of the Grand Duke and his ministers to what was happening, but Ferdinand himself no longer wanted to give the patronal feasts civil and political character, even refraining from participating in them.

THE LEOPOLD YEARS

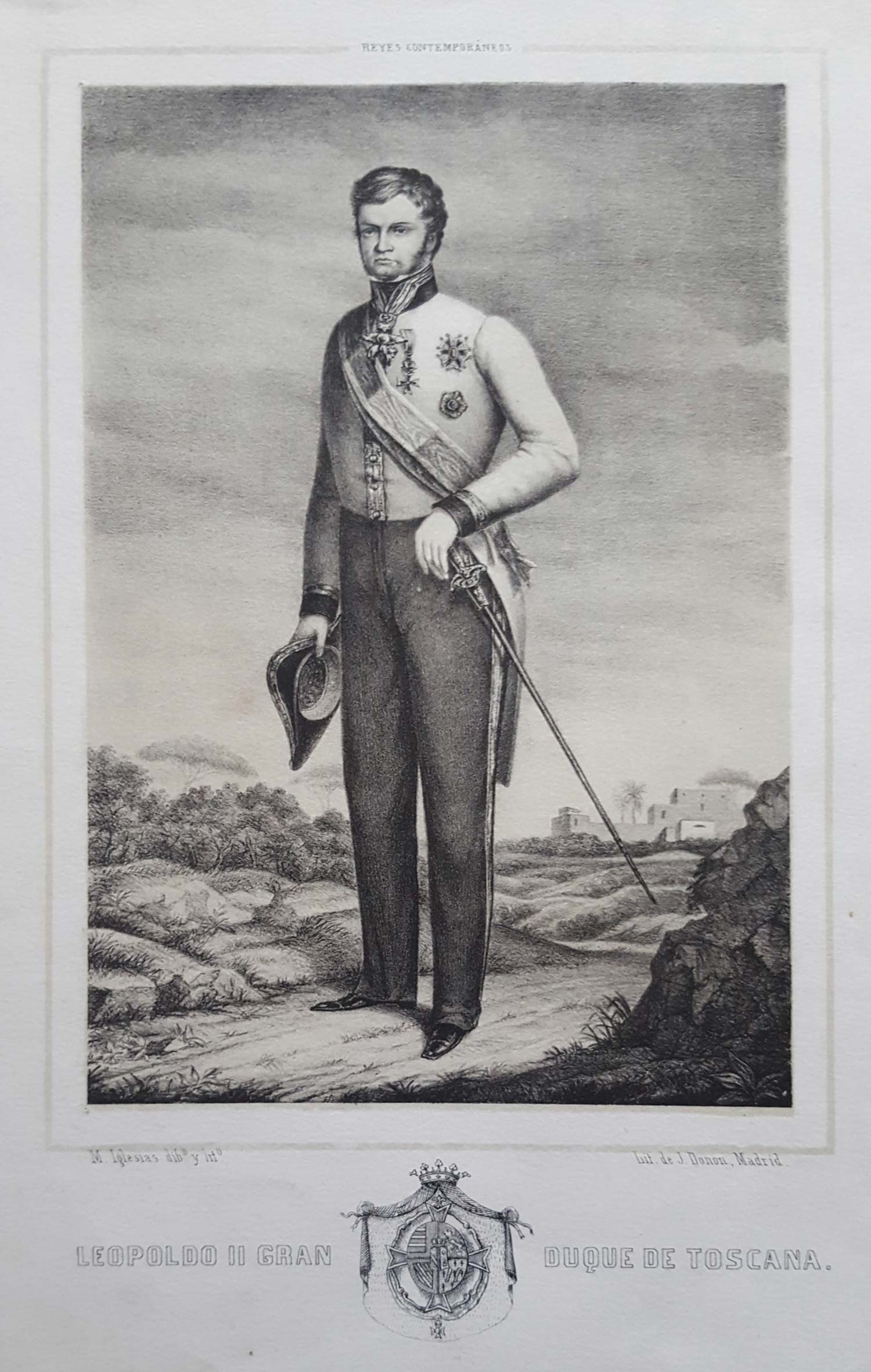

The Society of St. John the Baptist continued its activity, working closely with the Florentine church and only with the rise of Leopold II was there a sign of change.

A new petition, sent to court by the Deputies of the association in 1826, had an unexpected result and the young Grand Duke announced that he wanted to attend the feast in honor of St. John.

The years of Leopold II marked one of the highest moments of the Florentine association: the number of members grew steadily and in 1831 even the sovereign of Piedmont, Carlo Alberto di Savoia, asked to be part of the institution.

In 1839 Leopold II, to connect even more permanently the Society of St. John the Baptist with the grand-ducal institutions, conferred on the association the honorary title of imperial and royal.

ITALIAN INDEPENDENCE

Times were rapidly changing, politically, and in 1848 Leopold II granted constitutional status.

The war against Austria also saw the participation of Tuscan units and in the session of June 10, 1848 the Society of St. John the Baptist established, with plurality of votes, that as regards the dowries to be assigned “should be preferred, as far as possible, the families belonging to the Tuscan volunteer soldiers”.

As can be seen, the leaders of the association were animated by a strong patriotic spirit: the Society, however, remained cautious in the political openings of obvious rupture. The experience of the provisional government of Guerrazzi, Montanelli and Mazzoni was opposed and in May of ’49 the Deputies wanted to testify to Leopold II, temporarily refugee in Mola di Gaeta, their devotion.

However, in 1849, the feast of St. John took place without Leopold II, still far from Florence. The association testified in the clearest way the desire to perpetuate a tradition that went beyond any political contingency and the Florentines lived with the same spirit the celebration of their patron.

But the fracture of 1849, reiterated in 1852 with the very serious abolition of the constitutional statute shortly before granted, fatally weakened the image and power of Leopold II. Something had been irretrievably destroyed and the very life of the Society of St. John began to languish.

When Vittorio Emanuele II of Savoy was proclaimed “King elect”, the feast of the patron saint took on essentially religious connotations: a world of traditions and local history was about to disappear and in 1860 the Society of San Giovanni was reduced to only 300 members.

BIRTH OF THE KINGDOM OF ITALY

The proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, on March 17, 1861, marked the consecration of a completely new political horizon.

The strong secular imprint that pervaded the Risorgimento culture had given an irreversible turn to every institution but, in 1865, Florence was proclaimed the capital of the kingdom and even its patron had new splendor.

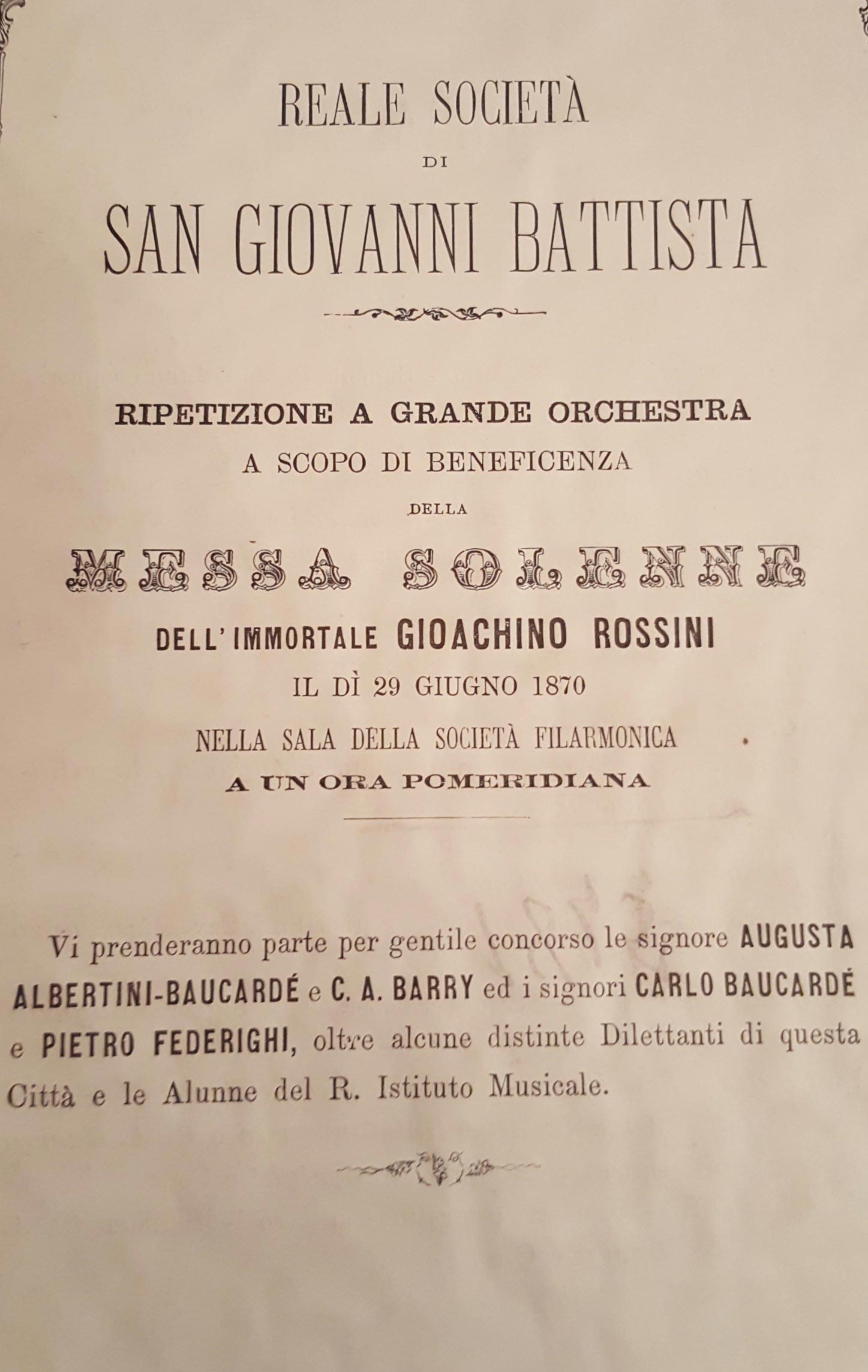

Slowly, starting from 1866, the members of the San Giovanni grew in number and it was again possible to distribute the money for some dowries and perform worthy musical performances: on June 24, 1870 a solemn mass by Gioachino Rossini, directed by maestro Teodulo Mabellini, sanctioned the new face of the Florentine association and not even the capture of Rome – and the subsequent transfer of the capital to the eternal city – slowed down the rebirth of the Society of San John the Baptist.

The number of members grew steadily reaching, in 1872, the considerable figure of 657: music, dowries, alms and fireworks had new vigor and in the same years they began to press the Ministry of the Interior for the Society to be transformed into a Moral Body with legal personality.

Although the transformation was not granted, the Society of St. John ended up assuming an important role of liaison between the Town Hall and the Archbishopric as well as maintaining a privileged relationship with the House of Savoy, which

he contributed money to the work of the institution.

The killing of Umberto I, in July 1890, was a hard blow.

The Society of St. John the Baptist began to decline and enrollment decreased dramatically: in 1908, the members were only 584.

CONTEMPORARY AGE

The First World War caused a serious economic crisis that made life extremely difficult for ancient cultural associations.

In 1923 it was not possible to set up the traditional fireworks show and the new political orientation did not prove sensitive to those traditions that had always found their natural referent in the world of the church.

The Silver Octagon

The Society of St. John the Baptist managed to survive but not to return to the glories of the past although Benito Mussolini was quickly included among its honorary members: only in 1927, with the greater involvement of the Fascist Party within the association, something changed. In 1929 a radical reform of the Social Statute was implemented, in close harmony with the ideological climate of the moment, and the Concordat brought a new spirit of collaboration by introducing curious initiatives such as announcing June 24 with ten mortar shells fired from Forte Belvedere. The members again reached one thousand units and it was decided to establish a library of historical-Florentine character within the association.

The years of the Second World War saw the San Giovanni engaged essentially on the front of assistance and fraternal aid and, with peace, rediscovered its ancient vocation: music offered a bridge to overcome any ideological division and concerts and performances were added to fireworks and religious ceremonies. Awards to illustrious Florentines, exhibitions and conferences have highlighted a new face of San Giovanni which, with the support of the Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze and its Foundation, has always honored the heavy commitment of organizing the patronal feasts.